History Of The Ho Chi Minh Trail-Route 20

HISTORY OF THE HO CHI MINH TRAIL – ROUTE 20

By Virginia Morris . 20 September 2023 Pictures By Clive Hills

Route 20 in Laos is an historic part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail and when I first went there in

the late 1990s it looked as if the war had not long ended. Villages were built from metal,

either rusting bomb casings or shiny aluminum from flares pods and aircraft parts. Vegetables

grew in cluster bomb casings. Foxholes were evident around villages. Lorry ruts disappeared

into maturing trees. There was even a temporary jungle graveyard for soldiers just off the

main path. War was everywhere.

To get into this part of Laos you needed a good guide to arrange your government

paperwork to do so. I travelled with Clive, a photographer and now my husband and Mr

Vong. Looking back, Mr Vong enabled me to follow my dreams and put up with me pushing

to go just that little bit further. During those days, was the government paperwork there to

keep you safe or to hide what the authorities did not want you to see? Probably a bit of both, I

had concluded, because Mr Vong would answer when I had asked about sensitive topics, ‘I

don’t know it’s my first time too’.

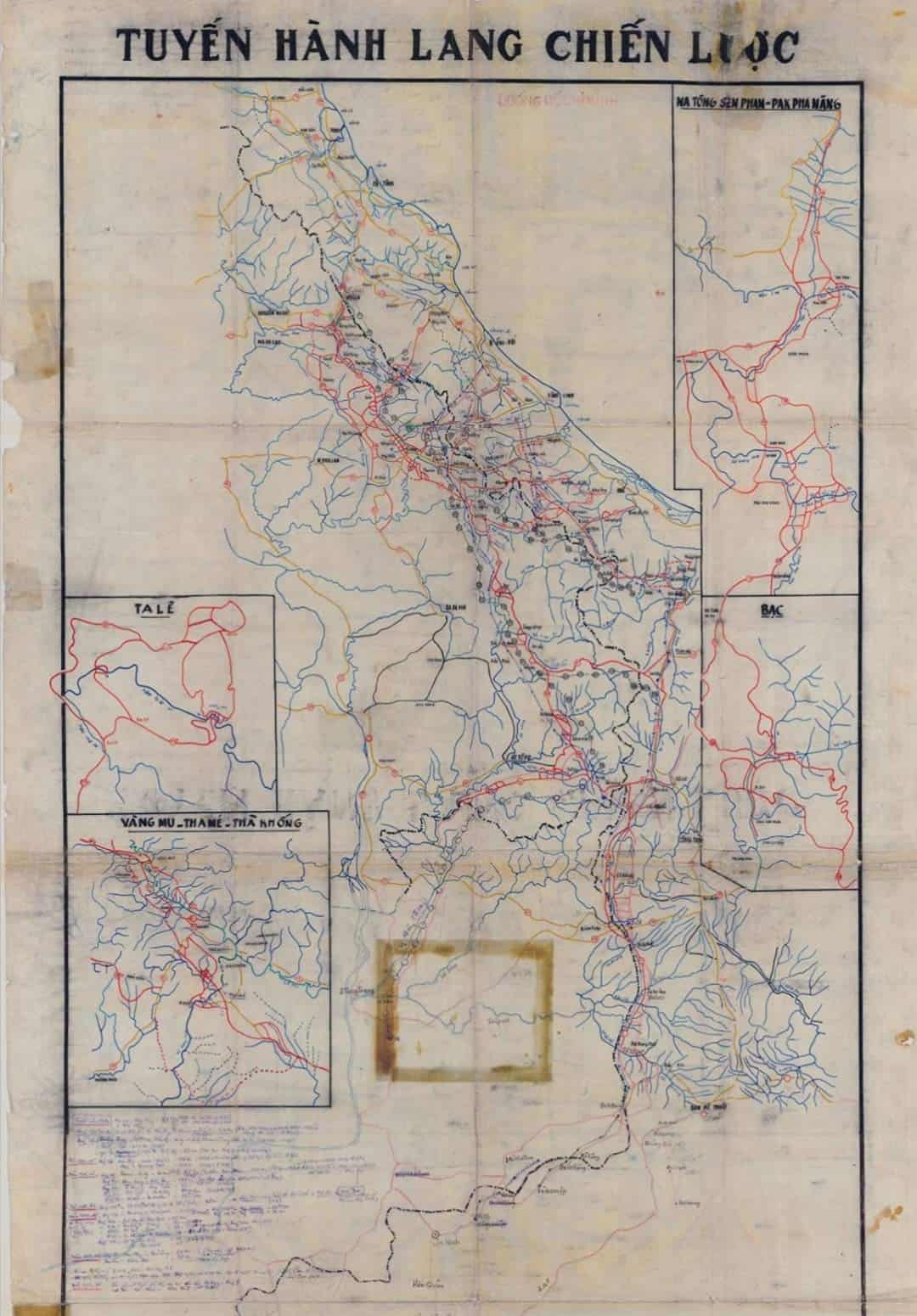

Construction started on Route 20 in 1966 because other roads were too vulnerable to

American bombing. This meant that Route 20 was not just one road but several, including

bypasses and secret K roads. It became one of the most important crossing points from North

Vietnam into Laos and sat between Route 12 to the north and Route 18 to the south.

Nevertheless, on completion Route 20 too was bombed day and night and earned the nick

name the Desert of Fire. Part of the problem was, it wove through the ATP – A for the A

bend in the road, P for the Phu La Nhich Pass and T for the Ta Le River. This hotspot for US

bombing raids started no sooner had a truck driver crossed the border from Vietnam to Laos and carried on into the Lum Bum area, were the headquarters of Army Station 32 was

located.

We walked through the ATP because in the late 1990s the road was not always passable for

even rudimentary traffic. During the wet season, trucks could not travel but even when the

weather improved there was limited access through to Vietnam. We met a truck driver who

travelled Route 20 year in year out, his vehicle caught on the same stretch of road since the

trees had grown and blocked him in. Occasionally, we came across a live bomb buried into

the ruts he passed over, the yellow ring around the metal body still visible, how they never

exploded I did not know but I was sure that one day that truck driver would find out the hard

way.

The image that has remained with me is that of a new village, sat within the Desert of Fire.

At the point in question, the road was elevated, and this new village formed just a small red

dust plot on the vast green plateau floor, all set to the backdrop of limestone karsts which

encompassed the Phu La Nhich Pass. The settlement was so new that it did not have a name,

and I have vivid remembrance of it because it typified the struggles of people after the war.

The village chief had welcomed us to his home. I could see that the wooden framed houses

on stilts took up the only level areas and the rest of the village comprised bomb craters filled

with sludge water. Few farm animals foraged between huts. No vegetable patches had been

planted to supplement the villagers’ diet. It felt like the village had been delicately placed on

the ground, so as not to disturb a sleeping beast.

Our Lao guide politely sat and ate with the chief, while Clive and I took a walk to excuse

ourselves from the sticky rice, chili and the off-smelling meat. Paths fanned from the village,

and we headed for the first one we saw leading towards the distant karsts. Weaving our way

through the low brush and bomb craters, the silence suddenly broke, and Mr Vong shouted

our names and instructions. Lao seldom shout, so with his urgency we lost our planned route back and our carefree approach. Looking to the ground to guide my feet, I could see that the

craters were so tightly packed that in places just a narrow width of even ground was left to

walk on. Within the craters, hidden in the sludge, was twisted metal and bombs. When the

undergrowth was disturbed by my feet, the debris of war revealed itself.

From his long chat with the chief, Mr Vong realized why the village was so sparse. These

people hunted and scavenged in the forest; he had told us on our return. What should have

been their rice paddies, was a minefield scattered with unexploded weaponry. The grazing

land for their cattle and the waterholes for them to drink from – poison.

Today Route 20 is very different. The bombs have mostly been cleared and it is open for

tourists to travel. It is a little known must see in Laos. Clive and I hope that one day we can

travel with our two children along Route 20 and experience its development since those

magical days with Mr Vong.